In praise of randomness

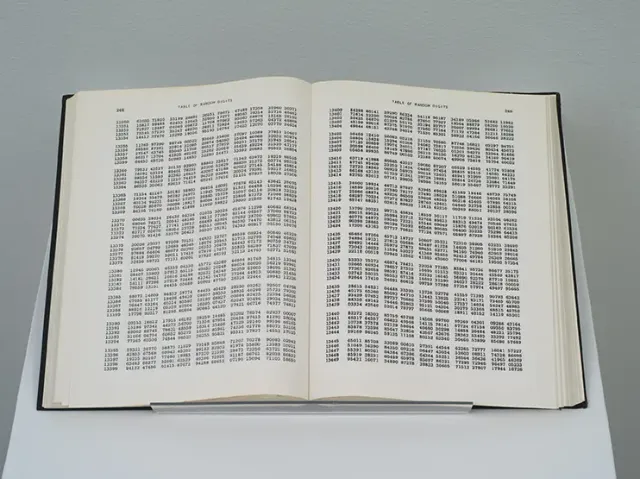

I have to admit that the first time I ever encountered the book A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates I was incredibly perplexed. Cracking the cover of this 400-page tome, originally published in 1955 by the RAND Corporation, I found it contained nothing but page upon page of 50-digit random numbers, each split into columns of 5. There was not much text to speak of, very little description, no narrative.1 What, I wondered, was the purpose of such a book?

At the time, I was a graduate student at UC Irvine studying art and computer science. A colleague of mine, Tom Jennings, had brought the book with him to complement an exhibition of his new work, a random number generator he had built using a geiger counter and a small piece of radioactive material. Tom explained that the book was necessary—at the time it was published—for things like Monte Carlo simulations, and was produced by RAND for scientific purposes, most likely for nuclear fission simulations. Writing about the book on his website, he comments on its sheer oddity:

This is a strange book, possibly the oddest book I own, and I have a few oddballs on my shelves. On it’s face, it’s a rigorous mathematical table, the intended audience those working in specialized mathematical fields, so it’s strangeness is not that obvious …

The suggestions for use of the tables reads as a bizarre magical rite, outside its mathematical context: “…open the book to an unselected page… blindly choose a 5-digit number; this number reduced modulo 2 determines the starting line; the two digits to the right… determine the starting column…”, complete with suggestions on avoiding the obvious pitfalls of books that fall open to the same page, human tendencies to choose numbers in the middle of a page, etc, all precisely the opposite of how mathematical tables are used. And it’s of course perfectly, verifiably correct.

Recently, I found myself thinking about Tom and this strange book while reading James Bridle’s excellent Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines and the Search for a Planetary Intelligence. Bridle devotes an entire chapter of this book to the subject of randomness and the myriad ways it is essential to life, intelligence, and both human and non-human creativity. On the immense, often under-appreciated value and importance of randomness, they write:

… randomness underlies the entirety of evolution, providing the impetus for some of its most extraordinary and captivating forms. It also plays a central role throughout our individual and collective lives and the lives of more-than-human others. Our lives are themselves random: chance encounters, events and the accumulation of accidents being the defining feature of our span upon this Earth.

Computers, of course, are incapable of true randomness. Most computer programmers know this, though they rarely concern themselves with this pesky little detail. But it was precisely this fundamental limitation of computing that my grad school colleague Tom was trying to circumvent with his geiger counter. And it’s the same limitation that the RAND corporation was trying overcome in the creation of the “electronic roulette wheel” it used to produce the random numbers in that strange, 400-page book.

Bridle discusses, at length, the incompatibility of true randomness and computing. They write:

True randomness is a slippery thing: it is a property not of things in themselves, like individual numbers, but of their relationship to one another … The problem computers have with randomness is that it doesn’t make mathematical sense. You can’t program a computer to produce true randomness—wherein no element has any consistent, rule-based relationship with any other element—because then it wouldn’t be random.

In most programming contexts where randomness is necessary, algorithmically-generated pseudo-randomness will suffice. But, there are a few critical contexts—cryptography or lotteries, for instance—where true randomness is absolutely necessary. And this is where computers, as standalone devices whose inner workings are mostly insulated from the chaos of the outside world, pose a problem. In these cases, we must inject randomness into them from the outside, using “fluctuations in the atmosphere, decaying materials, shifting globules of heated wax and the quantum dance of the universe itself.” As Bridle observes:

In order to be full and useful participants in the world, computers need to have relations with it. They need to touch and be in touch with the world.

We could all benefit from more randomness in our lives more than we may realize. By veering off the beaten path, by being exposed to new things we would otherwise never expose ourselves to, we increase the possibilities for serendipitous and creative encounters. But our increasingly computationally-dependent world is fundamentally incompatible with allowing this to happen. In fact, it often actively conspires against it. Consider, for instance, how search engines act as a force for the reduction of serendipity. On this, Bridle writes:

The first search engines were hand-curated lists of interesting places, essentially random accumulations of sites and tools ordered only by the passions and peccadilloes of those who assembled them. While Google still searches the web with automated random walks, its results are ordered by deeply partisan algorithms, with the top results sold off to the highest bidder. Google has almost a 90 per cent share of the world’s web searches, yet indexes only a tiny fraction of the visible web. Most searchers never look beyond the first page of results. There is little room for randomness in exploring the vast information available to us. This is deliberate.

The same is true in numerous other contexts. In bringing order to our complex world, computing constantly attempts to further homogenize our lives, to bring sameness to everything we do, everything we buy, everywhere we go:

So many of our tools are designed to reduce randomness in a similar fashion: from algorithmic recommendation systems to dating apps, from GPS navigation to weather forecasting. Each of these technologies—with the best of intentions—attempts to draw clear lines through a complex environment and provides us with a route to our desires free from obstructions, diversions and the vagaries of chance and unforeseen encounters.

It’s also worth contemplating this in the context of generative AI. Randomness turns out to be critical for machine learning, for instance. Gaussian noise, a kind of random noise signal that follows a Gaussian or normal distribution, is used when training machine learning models to improve robustness and prevent overfitting. This randomness is necessary to ensure that AI can handle the kinds of fuzzy, imprecise input we humans automatically handle without difficulty.

The output of generative models often feels random, almost like a slot machine. Given the same prompt you can and will get multiple variations of output from the same model. But a closer inspection reveals that generative AI, too, can act as a force for homogenization. Nothing any model produces is truly random. After all, generative AI is only novel insofar as its training data allows, which means it can only “remix” that which it has already “seen” in the past. It feels novel to us because none of us has seen nor read the entirety of the Internet. To use Margaret Boden’s terminology, generative AI is more P-creative than H-creative.

Towards the end of their chapter, Bridle reminds us how critical randomness is to the experience of life itself:

… meaning resides less in the data at the end of the path and more in the path travelled. We learn, change, develop and grow when we move and entangle ourselves with the world in unexpected ways, and we do so best when we are fully engaged participants in that journey, not passive recipients of algorithmic and corporate diktats.

Randomness matters in more ways than we often appreciate. And as computing comes to dominate more and more of our lived experience, I find myself wondering if we can we find more ways to keep the beauty of chance encounters and experiences alive and well for us all. (And, perhaps, unlike my friend Tom, we might be able to do so without the mild dose of radiation.)