Ivan Illich on how technologies create radical monopolies

As society moves to replace what have traditionally been analog processes and infrastructure with digital equivalents—a phenomenon rapidly accelerated by COVID-19 and our desire for “touch free” interaction—it has become increasingly difficult to get by without access to a smartphone. From restaurants foisting QR codes for access to menus on patrons, to digital boarding passes, to museum and concert tickets now requiring bespoke apps, smartphone ownership is often a deciding factor for access to many cultural experiences, or at the very least, a differentiator in the level of service one now receives in a multitude of commercial interactions. What’s worse, this is compounded by the fact that owning just any smartphone is often insufficient—one must own a smartphone tied to one of only two major application ecosystems: Apple’s or Google’s.

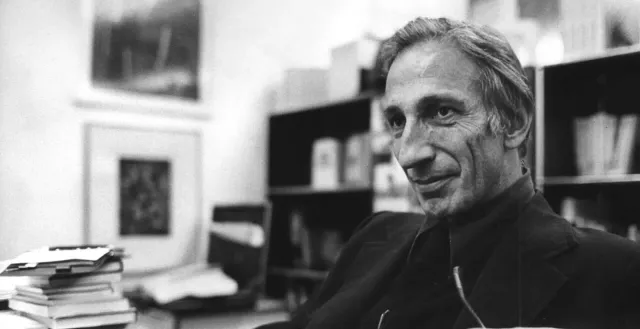

In 1973, cultural critic Ivan Illich (1926-2002) warned us about this phenomenon in Tools for Conviviality, calling the exclusive control a technology can come to exert over aspects of daily living a “radical monopoly.” Defining the term, he wrote:

Generally we mean by “monopoly” the exclusive control by one corporation over the means of producing (or selling) a commodity or service … By “radical monopoly” I mean the dominance of one type of product rather than the dominance of one brand. I speak about radical monopoly when one industrial production process exercises an exclusive control over the satisfaction of a pressing need, and excludes nonindustrial activities from competition … The establishment of a radical monopoly happens when people give up their native ability to do what they can do for themselves and for each other, in exchange for something “better” that can be done for them only by a major tool.

Smartphones did not exist in 1973 of course. But Illich gives us an example of another familiar technology that now exerts a radical monopoly over modern daily living: the automobile. Over mere decades, the proliferation of the automobile radically altered the infrastructure of cities so that they were designed to best accommodate this single mode of transportation, often to the exclusion or detriment of other, more ecologically sound alternatives—namely, walking, bicycling, or public transportation. Especially in the US during the middle and latter half of the 20th century, cities were developed with ever-wider roads, longer blocks, limited or non-existent sidewalks, encircling superhighways, and vast sprawl that was impossible or extremely inconvenient to traverse without access to a car. Commenting on this, Illich wrote:

Cars can thus monopolize traffic. They can shape a city into their image—practically ruling out locomotion on foot or by bicycle in Los Angeles … Of course they are dangerous and costly. But the radical monopoly cars establish is destructive in a special way. Cars create distance. Speedy vehicles of all kinds render space scarce. They drive wedges of highways into populated areas, and then extort tolls on the bridge over the remoteness between people that was manufactured for their sake. This monopoly over land turns space into car fodder. It destroys the environment for feet and bicycles.

The physical infrastructure required for human transportation possesses a high degree of inertia—it is very difficult and costly to undo—creating a flywheel effect of increased dependency and further development of the same kind of infrastructure. The result is a kind of technological lock-in to a single way of being. As Illich wrote:

Monopoly is hard to get rid of when it has frozen not only the shape of the physical world but also the range of behavior and imagination. Radical monopoly is generally discovered when it is too late.

Moving beyond transportation, Illich argued that radical monopolies have also developed in other industries and sectors, including education (schools), healthcare (hospitals and professional medicine), and even the simple act of burying of the dead (undertakers). His examples and arguments against radical monopoly compose but a small part of his much broader argument against industrial productivity in favor of what he called “conviviality,” a way of being in the world emphasizing personal autonomy, interdependence between individuals, and freedom from imposed dependence on industrially-produced goods or services. A society is convivial, argued Illich, if people have the freedom to jointly shape and create things in mutual interdependence with each other and with nature. Or, in Illich’s own words:

I choose the term “conviviality” to designate the opposite of industrial productivity. I intend it mean autonomous and create intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment; and contrast this with the conditioned response of persons to demands made upon them by others, and by a man-made environment … A convivial society should be designed to allow all its members the most autonomous action by means of tools least controlled by others.

The radical monopoly of any technology is thus anti-convivial because it restricts personal autonomy and increases dependence on the few producers of that technology and its associated infrastructure. Cars create car infrastructure and thus car dependence, increasing the wealth of car producers, and exacerbating class stratification between car owners and those who do not own cars. Education, argued Illich, operates similarly. Schools create the need for more schooling, with the requirement of a degree for many employment opportunities discriminating against autodidacts and the unschooled (capability and skills being otherwise equal).

We now see something similar happening with smartphones. As smartphone-oriented infrastructure continues to seep into everyday life, it begets ever-greater dependence on smartphone technology, and thus ever-greater dependence on the producers of this technology. Those who cannot afford smartphones, or those who simply choose to live without smartphones, find themselves increasingly excluded from full participation in society, often with no viable alternative. Like with the automobile, we may soon become locked into this way of being. Perhaps we already are.

If you’re looking to dig into more of Illich’s ideas and philosophy beyond Tools for Conviviality consider the work and writing of Illich scholar L.M. Sacasas, including his excellent newsletter, The Convivial Society, as well as his interview discussing Illich on the Hope in Source podcast.